Source

| Title | 2024 Pest Management Strategic Plan for Crapemyrtle in the South |

| PDF Document | https://ipmdata.ipmcenters.org/documents/pmsps/Crapemyrtle2024PMSP.pdf |

| Source Type | Pest Management Strategic Plan |

| Source Date | 11/26/2024 |

| Workshop Date | 10/08/2024 |

| Workshop Location | Online |

| Settings | Crapemyrtle |

| Region | Southern |

| States | Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas |

| Contacts | Hongmin Qin, Texas A&M University, hqin@bio.tamu.edu Bin Wu, Texas A&M University, bin.wu@tamu.edu Runshi Xie, Texas A&M University, fushe001@email.tamu.edu |

| Contributors | Jim Berry, Jimberry Nursery Yan Chen, Louisana State University Hui Duan, USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Steven Frank, North Carolina State University Midhula Gireesh, University of Tennessee Frank Hale, University of Tennessee Derald Harp, Texas A&M University David Held, Auburn University Hazen Keinath, Texas A&M University Xavier Martini, University of Florida Laura Miller, Texas AgriLife Extension Service Jeremy Pickens, Auburn University Nar Ranabhat, University of Tennessee Joseph Shimat, University of Georgia Erfan Vafaie, Texas A&M University |

| Citation | Qin H, Xie R, Wu B. (2024). Pest Management Strategic Plan for Crapemyrtle in the South. National IPM Database. https://ipmdata.ipmcenters.org/source_report.cfm?view=yes&sourceid=2543 |

| Preview Sheet |

Executive Summary

The 2024 Pest Management Strategic Plan (PMSP) for Crapemyrtle was developed to address key pest challenges and management strategies for crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia spp.) in the Southern United States. This PMSP is the result of a virtual stakeholder meeting held on October 8, 2024, bringing together nursery growers, landscape professionals, university extension specialists, entomologists, plant pathologists, industry representatives, and regulatory agencies to identify the most pressing pest issues and establish research, regulatory, and educational priorities for sustainable pest management.

This PMSP covers the Southern IPM Region, including Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas. The meeting was facilitated by researchers from Texas A&M University, University of Tennessee, Louisiana State University, University of Georgia, and North Carolina State University, with additional participation from representatives of the EPA, USDA Office of Pest Management Policy (OPMP), and the Southern IPM Center (SIPMC).

Economic and Regional Significance of Crapemyrtle

Crapemyrtle is a widely cultivated ornamental tree in the southeastern United States, valued for its low maintenance and vibrant floral displays. It is extensively used in residential and commercial landscapes, city streets, and parks. The wholesale and retail market value of crapemyrtle exceeds $70 million annually, making it an economically significant plant in the U.S. nursery and landscape industries. However, emerging invasive pests, such as crapemyrtle bark scale, threatens its sustainability, prompting the need for improved Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies.

Key Pests

Insects

Crapemyrtle aphid (Sarucallis kahawaluokalani)Crapemyrtle bark scale (Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae)

Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica)

Whitefly (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae)

Pathogens

Powdery mildew (Erysiphe)Pseudocercospora leaf spot (Pseudocercospora spp.)

Sooty mold (general)

Weeds

Nutsedge (Cyperus spp.)Pigweed (Amaranthus spp.)

Spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata)

Crops/Settings

Description

Crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia spp.) is a versatile and low-maintenance flowering shrub or small to large tree that is commonly used in home landscapes, community developments, and as street trees. Multiple common names or spellings (e.g., crape myrtle, crepe myrtle, or crapemyrtle) existed when people refer to Lagerstroemia spp. However, the use of ‘crapemyrtle’ may avoid the confusion of Lagerstroemia (in the Lythraceae family) as a ‘myrtle’ plant (in the genus Myrtus and Myrtaceae family).

Crapemyrtle is native to East Asia but is now cultivated in many parts of the world. In terms of market demand, crapemyrtle is a popular plant among landscapers, gardeners, and homeowners, particularly in the southern United States. The plant is sold in various sizes and colors, with the larger and more mature specimens commanding a higher price.

Crapemyrtle is also used as a hedge, screen, or specimen plant. One of the most attractive features of crapemyrtle is the abundant summer color, which the plant blooms in a range of colors, including red, pink, lavender, and white. Its adaptability to a wide range of soil types and its tolerance for drought (after being established) make it a popular choice for landscaping. It is ideally suited for community plantings due to its long life and ease of management. However, the plant is also susceptible to several pests and diseases, such as scales, aphids, powdery mildew, and sooty mold, which can be managed through proper cultural practices and the use of appropriate pesticides.

Overall, crapemyrtle is a versatile and valuable crop with broad appeal in the ornamental plant industry. Its ease of cultivation, attractive appearance, and adaptability make it a desirable addition to any landscape or garden.

Vegetative architecture

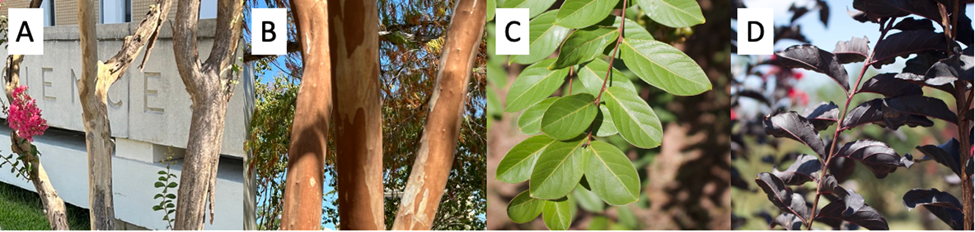

Though more commonly adored for its floral blooms, as discussed below, there is much to be desired in the vegetative appearance of crapemyrtle. Though variable in size, depending on cultivar, crapemyrtles are densely branched and often multi-stemmed. Surrounding the stems, crapemyrtle has a unique bark that peels each year, revealing the new growth beneath. In some varieties, the revealed wood can appear reddish in tone, varying in color from the peeling bark. This aesthetic pairs well with the dense foliage surrounding the tops of these plants. The leaves grow from alternate nodes, each developing into a lanceolate shape that features entire margins and palmate venation. Leaf size can vary with the size of the plant; both shrubs and large tree varieties of crape myrtle are available. Additionally, there are common cultivars exhibiting fully darkened vegetative tissue. More specifically, the bark and leaves exhibit a dark purple color attributed to high anthocyanin accumulation. In some cases, this fades with maturity, but most sed varieties persist in color. Examples of darkened cultivars include the Ebony or Black Diamond™ series.

Figure 1: Common crapemyrtle vegetative structure traits. A) The most common bark color and an example of peeling bark. B) An example of the reddish bark available in some cultivars. C) The typical leaf pattern and shape found among crapemyrtle; imaged is ‘Natchez’. D) An example of the darkened foliage; imaged is ‘Ebony Embers’. Photos by: Hazen Keinath.

Flower architecture

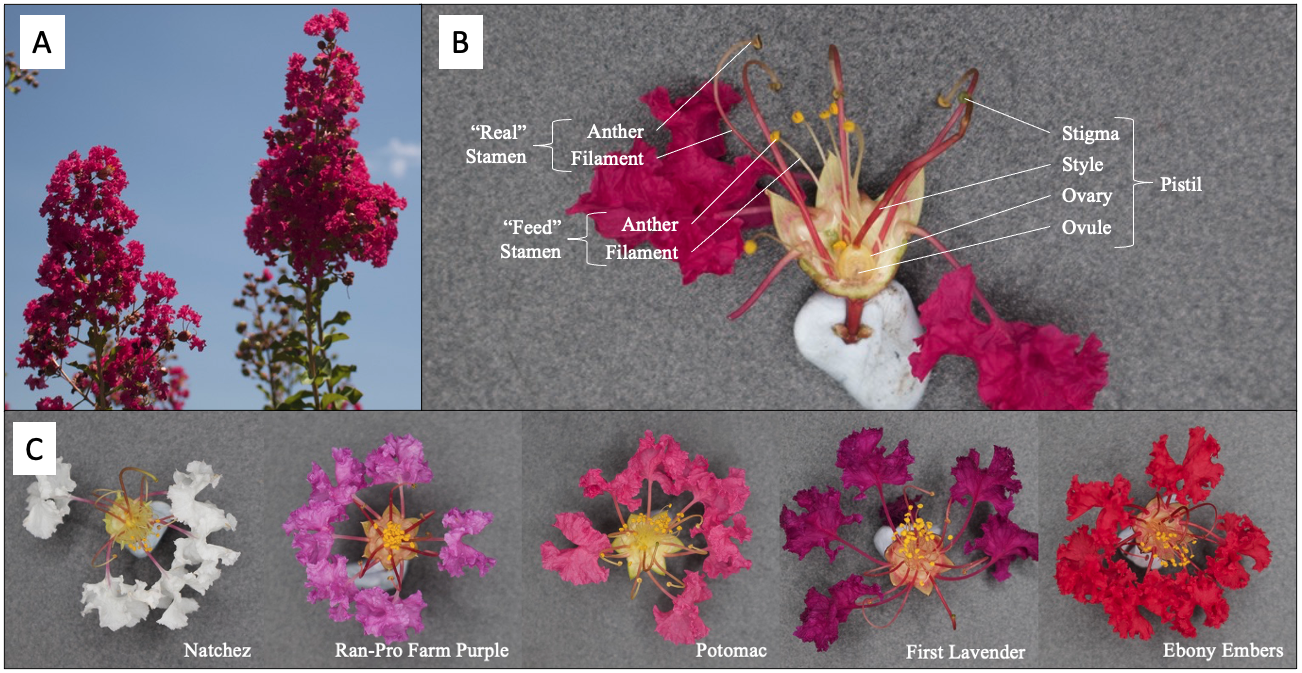

Crapemyrtles feature large, colorful blooms displayed on large pinacle inflorescence structures. These structures emerge from the ends of new growth, usually beginning the second year after germination. Each individual bloom features a perfect, hypogynous flower ranging in the deep purple to red to white petal color range. At its base, the flower’s calyx usually consists of six green sepals, deltoid in shape. The mainstay of crapemyrtle blooms are the unique crepe paper-like petals. Each corolla consists of five to seven spatulate petals crinkled toward their margin, each housed on a long stalk that extends past the sepals in length (Meerow, Ayala-Silva et al. 2015). Within the petals, many (up to 100) long stamens are clustered around the ovule. Each stamen typically consists of a yellow or light green anther held by a filament ranging in color from a yellow or light green to pink or red, depending on the cultivar. Especially among L. indica and its various hybrids, the flowers exhibit a heterantheric morphology, consisting of six elongated anthers that produce blue-green “real” pollen and a bundle of shorter, yellow anthers producing “feed” pollen for pollinators, such as bees (Nepi, Guarnieri et al. 2003). At its center, these flowers include a superior, globose ovary fitted with a long style that stands above the stamens. The pistil as a whole exhibits a light green color, paired with darker green tones as you approach the stigma. Additionally, it is common for the style to contain shades of pink or red along its length.

Figure 2: Crapemyrtle flower architecture and color range. A) Pinacle structures of crapemyrtle blooms. B) Cross-section of crapemyrtle, highlighting the reproductive organs (‘Sioux’ cultivar). C) Example flowers from various cultivars, as labeled. Photos by: Hazen Keinath.

Flower color

Most of the color of crapemyrtle blooms is the result of anthocyanin accumulation, or lack thereof, in the petals (Yu, Lian et al. 2021). Just like the crop of interest in this text, anthocyanins make up a family of closely related compounds, ranging on color from violet to red based on three major components: chemical structure, pH of the vacuole, and co-pigmentation effects with other flavonoids and metal ions (Alappat and Alappat 2020). Generally speaking, less chemically/metallically modified, lower pH anthocyanins exhibit red color, while the opposite produces violet or blue colors. Additionally, lesser amounts of anthocyanins in the petals can lead to lighter colors, such as pink or lavender, and a lack of anthocyanins can produce white varieties. Current crapemyrtle cultivars available cover almost every flower color produced by anthocyanins, with the exception of blue, which is rare amongst flowering species. Below are listed a few common examples of colors available and example cultivars (examples gathered from Crape Myrtle Trails).

Red: Dynamite, Arapaho, Ebony Embers

Purple: Twilight, Powhatan, Catawba

Lavender: Muskogee, Byers Hardy Lavender, Yuma

Pink: Tuscarora, Potomac, Miami

White: Natchez, Sarah’s Favorite, Acoma

Even among the broad categories listed above, there is abundant variation in the specific colorations between crapemyrtle lines. Though there is an abundance of color options available, there are still many colors yet to be produced. The only anthocyanin-based petal color missing in the range is blue, which is notoriously rare among flowering plants (Dyer, Jentsch et al. 2020). In addition, there are yet to be any cultivars exhibiting non-anthocyanin colors, such as yellow and orange.

Crop growth stages

Dormancy

As a deciduous species, crapemyrtle will drop its leaves and enter a period of dormancy during the winter months where it stops growing and conserves energy for the upcoming growing season. The timing of leaf-drop can vary depending on factors such as weather patterns, temperature, soil moisture, and the specific species or cultivars of crapemyrtle planted. The process of leaf dropping can be accelerated when the crapemyrtle is under stress, such as drought or insect infestation.

Bud break and vegetative growth

In spring, when temperatures start to rise, the buds on Crapemyrtle branches begin to swell and open up, signaling the start of new growth. The onset of new growth can vary depending on the age and location of the plant, with more established and full-sun planted crapemyrtles generally waking up earlier than younger specimens. Sometimes, crapemyrtle can take a bit longer to push out foliage in late spring or early summer. During this stage, the crapemyrtle puts on new leaves, stems, and branches. It is important to provide adequate water and nutrients during this stage to support healthy growth.

Flowering and seed development

Crapemyrtle will produce an abundance of colorful blooms that can last for several months in the summer. The flowering time for crapemyrtle can vary depending on the specific cultivar and weather conditions in a given year. In general, flowering typically begins in late spring to late-summer, with peak bloom occurring from mid-July to mid-August. After the flowers have faded, the crapemyrtle will produce fruit in the form of small oval capsules that contain numerous winged seeds.

Senescence

As temperatures begin to cool in the fall, the crapemyrtle will begin to slow its growth and prepare for dormancy.

Growth habits

Crapemyrtle is one of the most versatile plants because of the various options in terms of plant and growth habits. Below are different crapemyrtle cultivars categorized in their heights.

Tall (20 ft. or more)

Example: Basham’s Party Pink, Biloxi, Byers Standard Red, Byers Wonderful White, Carolina Beauty, Choctaw, Fantasy, Hardy Lavender, Kiowa, Miami, Muskogee, Natchez, Potomac, Red Rocket, Townhouse, Tuskegee, Tuscarora, Wichita.

Semi tall (10 to 20 ft.)

Example: Apalachee, Catawba, Centennial Spirit, Cherokee, Comanche, Conestoga, Lipan, Near East, Osage, Powhatan, Raspberry Sundae, Regal Red, Royal Velvet, Seminole, Sioux, Wm Toovey, Yuma.

Shrub (5 to 10 ft.)

Example: Acoma, Caddo, Hopi, Pecos, Prairie Lace, Tonto, Velma’s Royal Delight, Zuni.

Dwarf (3 to 5 ft.)

Example: Baton Rouge, Bayou Rouge, Bourbon Street, Chica Pink, Chica Red, Chicasaw, Cordon Bleu, Delta Blush, Lafayette, New Orleans, Petite Embers, Petite Orchid, Petite Pinkie, Petite Plum, Petite Red, Pink Ruffles, Petite Snow, Pocomoke, Victor Deep.

Soil types

Crapemyrtle is a hardy plant that can tolerate adverse soil conditions, but it will grow and flower much better when planted in well-prepared soil. Crapemyrtle can adapt to a range of soil types, including clay, sand, and loam. It can also tolerate a range of soil pH levels, including alkaline and acidic soils. While crapemyrtle can grow in a variety of soil types, well-drained soil is preferred. Poorly drained soil creates an environment conducive to the development of root rot and the poor aeration of root zone compromises the overall health and vigor of the crapemyrtle (Knox 2006).

Crop Stages

| Order | Crop Growth | Stage | Days After Emergence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Sprout | Delayed Dormant (Bud Breaking) | |

| 3 | Vegetative | 6- to 12-Inch Shoot | |

| 4 | Flowering | Bloom |

Background

Crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia spp.) is one of the most popular deciduous flowering trees in the United States, generating an estimated market value of up to $70 million per year (USDA 2001, USDA 2009, USDA 2014, USDA 2019). Its versatility as an ornamental plant and long blooming period makes it a widely used choice in landscape.

Crapemyrtle also plays an important role in the local ecosystem in the southeastern United States (Riddle and Mizell III 2016). While the flowers do not produce nectar, they offer a significant source of pollen to attract pollinators such as bees (Harris 1914, Kim, Graham et al. 1994). Studies have shown that crapemyrtle pollen is a major protein source with a nutritional makeup that is suitable for bee consumption (Nepi, Guarnieri et al. 2003). The extensive and heavy blooming of crapemyrtle during summer months (Pounders, Reed et al. 2006, Pounders, Blythe et al. 2010) make it a critical food source for pollinators, especially when many other flowering plants are not in bloom (Lau, Bryant et al. 2019). Due to its wide distribution, crapemyrtle provides excellent pollen sources for both native and non-native bees in the United States.

Crapemyrtle is relatively easy to maintain in the landscape with few severe diseases and insect complications. However, pest issues such as aphids, scale insects, Japanese beetle, and metallic flea beetles, and diseases such as powdery mildew and Cercospora leaf spot (caused by Psedocercospora lythracearum) may require proper management.

Priorities

The top three education, regulatory, and research priorities were identified during the online workshop based on stakeholder input from growers, researchers, extension specialists, and industry representatives. These priorities reflect the most pressing pest management challenges facing crapemyrtle production and maintenance. Additionally, other unranked priorities were identified and included in this document to provide a comprehensive overview of current and emerging concerns.

In summary, workshop participants emphasized the need for targeted pest management strategies to reduce reliance on neonicotinoids, improve alternative control options, and enhance regulatory clarity for field-grown crapemyrtles. There is also a need for education on pest identification, sanitation practices, and application methods, along with research into resistant cultivars, effective treatment timing, and herbicide performance under variable environmental conditions. Overall, this document serves as a framework for guiding future research, regulatory decisions, and outreach efforts to support the crapemyrtle industry.

| Category | Rank | Pest Type | Pest | Crop Stage | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | No Rank | Develop standardized guidelines for tissue sample collection and analysis in field-grown crapemyrtles to enhance nutrient management and pest diagnosis. |

|||

| Education | No Rank | Educate growers and landscapers on the efficacy of mechanical control techniques. |

|||

| Education | No Rank | Provide ESA (Endangered Species Act) education for nurseries and landscape professionals. |

|||

| Education | No Rank | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Education on the status of breeding efforts for CMBS-resistant cultivars. |

|

| Education | No Rank | Insects | Whitefly | Provide education on whitefly jumping control strategies. |

|

| Education | No Rank | Insects | Promote pollinator and beneficial insect protection in crapemyrtle pest management. |

||

| Education | No Rank | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Develop CMBS sanitation guidelines to prevent further spread, including the survival duration of CMBS on equipment and best practices for decontamination before re-entering fields. |

|

| Education | No Rank | Weeds | Nutsedge | Develop guidelines for managing nutsedge without harming crapemyrtle trees. |

|

| Education | No Rank | Weeds | spotted spurge | Provide education on spotted spurge management. |

|

| Education | 1 | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Educate consumers and retail outlets about CMBS through campaigns, myth-busting, and available management options. |

|

| Education | 2 | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Improve landscaper communication to consumers regarding CMBS issues and control methods. |

|

| Education | 3 | Insects | Develop educational materials on modes of action for pest control products, including how applications work, effectiveness, and highlights of new chemicals. |

||

| Regulatory | 1 | Insects | Clarify label distinctions between container-grown and field-grown crapemyrtles for pesticide applications. |

||

| Regulatory | 2 | Insects | Assess the regulatory status of neonicotinoids and their alternatives for crapemyrtle pest management. |

||

| Regulatory | 3 | Insects | Determine the regulatory status of fertilization and insecticide combinations for crapemyrtle production. |

||

| Research | No Rank | Conduct research on ‘Rabbit Tracks’ as an abiotic stress affecting crapemyrtle growth. |

|||

| Research | No Rank | Study the timing and behavior of pollinators visiting crapemyrtle in late summer to guide pollinator-safe pest management. |

|||

| Research | No Rank | Insects | Examine the efficacy of mechanical techniques for pest control in crapemyrtle production and maintenance. |

||

| Research | No Rank | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Identify a dormant oil formulation that can effectively penetrate and control adult CMBS. |

|

| Research | No Rank | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Improve CMBS control strategies, including chemical, biological, and cultural management techniques that provide better runoff protection and reduce reliance on neonicotinoids. |

|

| Research | No Rank | Insects | Evaluate the efficacy and optimal application rates of insecticides (e.g., dinotefuran, imidacloprid) for field-grown crapemyrtles, comparing foliar, trunk, and granular treatments to refine dosage guidelines and improve pest control. |

||

| Research | No Rank | Pathogens | Pseudocercospora leaf spot | Investigate control strategies for pseudocercospora on crapemyrtle. |

|

| Research | No Rank | Weeds | Evaluate weed control costs associated with herbicide applications. |

||

| Research | 1 | Insects | Investigate insecticides other than neonicotinoids, including diamides, and assess their ecological effects on the surrounding environment. |

||

| Research | 2 | Insects | crapemyrtle bark scale | Develop CMBS-resistant varieties, ensuring pollinator protection and considering cold resistance in breeding efforts. |

|

| Research | 3 | Weeds | Study herbicide effectiveness under heavy rainfall or frequent irrigation (extends beyond crapemyrtles). |

Worker Activities

|

Production Practices |

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

Note |

|

Fertilization (Nursery) |

x |

x |

|

||||||||||

|

Pruning (Landscape) |

x |

x |

|

||||||||||

|

Pruning (Nursery) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Scouting (Nursery) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Scouting (Landscape) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Planting (Nursery) |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

||||

|

Planting (Landscape) |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

||||||

|

Irrigation (Nursery) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Irrigation (Landscape) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Propagation (Nursery) |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Production Practices

Crapemyrtle is a popular and versatile ornamental plant known for its vibrant flowers, wide range of color options, attractive bark features, and ability to thrive in various landscape settings. With its wide range of cultivars and adaptability to different regions, crapemyrtle has become a staple in gardens, parks, and residential and commercial landscapes.

To meet the market demand for crapemyrtle, the nursery industry utilizes field production and container production to produce crapemyrtle suitable for different landscape applications. Crapemyrtle plants are available in various sizes, ranging from small "liners'' or transplants to large caliper trees of 6 feet and larger. Smaller plants are commonly produced and sold in trays or containers, while larger trees are mechanically harvested as bareroot or balled and burlapped.

Field production involves growing crapemyrtle trees in the ground, typically in dedicated production fields. This method allows for the cultivation of larger specimens but requires specific management considerations for harvesting, transportation, and storage. However, notable issues regarding field production include the potential loss of field soil and root mass during the harvesting process for balled and burlapped plants.

On the other hand, container production involves growing crapemyrtle in pots or containers, providing flexibility in terms of space, mobility, and controlled environments. Container-grown crapemyrtle trees are more popular among retail nurseries, landscape professionals, and homeowners seeking smaller-sized trees for immediate impact. However, container production is limited when it comes to producing large caliper trees due to the maximum available container size, typically up to 500 gallons (Braman, Chappell et al. 2015).

Both field production and container production have their unique considerations and techniques, which are implemented by nursery professionals to ensure the successful growth, health, and market readiness of crapemyrtle trees. From site selection and soil preparation to propagation, irrigation, fertilization, pest management, and pruning, a comprehensive understanding of production practices is crucial for producing high-quality crapemyrtle specimens. In this section, the key production practices involved in both field-grown and container-grown production of crapemyrtle are outlined to provide valuable insights that contribute to the successful cultivation of crapemyrtle, enriching outdoor spaces with its beauty and charm.

Field Production

Site selection and soil preparation

Crapemyrtle thrives in sunny locations, making it essential to choose a bright and sunny spot for planting. Lack of sunlight can cause reduced flowering (Wade and Williams-Woodward, 2009), and cultivars that are known for their dark foliage tend to have greener foliage under a less sun conditions. The favorable growing c a great option for difficult locations that are hot and dry, where many other ornamental plants struggle to grow. When planting, spacing is a crucial factor to consider as some cultivars can grow over 20 feet tall, with a canopy spread between 5 to 20 feet (Niemiera, 2018). Limited planting space will lead to excessive pruning when the plant reaches its mature form.

As a woody ornamental, crapemyrtles are adaptable to various soil conditions and thus well suited for urban areas and even more challenging soils. Crapemyrtles grow best in soil that is heavy loan to clay texture with a pH between 5.0 to 6.5 (Egolf, 1987). While crapemyrtles can tolerate poor soils, the ideal soil should be nutrient-rich and well-drained, as poor soil can hinder growth and development. Proper preparation can ensure that the plant will have access to the necessary nutrients and water it needs to thrive. A soil test may be conducted to assess various soil parameters, including pH level, organic matter content, nutrient levels (such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium), micronutrient levels, and soil texture (proportions of sand, silt, and clay). Based on the findings, targeted soil amendments and fertilization can be done to optimize soil conditions for healthy crapemyrtle growth.

In nursery productions, additional factors such as operation space (turning radius for farming vehicles), topography (slope), and access to irrigation water need to be considered for site selection. A proper design of the planting rows and establishment of grassed waterways and buffer strips are effective in reducing soil losses and water runoff. Contour buffer strips of permanent, herbaceous vegetation should be established on sloping cropland and be at least 15 feet (4.6 m) wide to meet the conservation standards by USDA (USDA, 2014b).

Planting

Before planting, it is important to prepare the tree by removing any damaged or broken branches and roots. Digging the hole should be done at a depth that is slightly larger than the root ball. When planting, the root ball should be placed in the hole and back-filled with soil. It is important to avoid planting the tree too deep (no deeper than it originally grew in the container or field), as this can lead to poor drainage and hinder growth.

As an essential step in the planting process, watering is recommended for newly set transplants within 24 hours after planting to help firm soil around roots and eliminate air pockets (Braman et al., 2015). Newly planted trees need frequent watering to help establish roots and encourage growth. It is important to water thoroughly and consistently, ensuring the soil remains moist but not overly saturated.

Watering

Proper watering promotes the health and growth of crapemyrtle trees, and the watering requirements can vary depending on the growth stage and planting situation. Watering crapemyrtle at the base of the plant, not on the foliage, prevents the spread of foliar diseases. Additionally, watering in the morning or evening when the temperatures are cooler helps to reduce evaporation and water loss. Early morning (before 10 am) or late afternoon/evening (after 4 pm) are ideal for watering, as it allows sufficient time for foliage to dry before nightfall.

For newly planted crapemyrtle, it is important to water frequently in the first few weeks to help the tree establish roots. Watering should be done deeply, at least once or twice a week, depending on the weather conditions. A good rule of thumb is to water until the soil is moist to a depth of at least six inches. As the tree becomes established, watering frequency can be gradually reduced.

Established crapemyrtle trees in the landscape typically have deep root systems and can tolerate periods of drought without needing additional watering. They can often rely on natural rainfall to provide enough moisture, unless experiencing extended periods of drought. In such cases, supplemental watering may be necessary to prevent stress on the tree and enhance flowering (Wade and Williams-Woodward, 2009). It’s important to monitor soil moisture levels and only water when the soil is dry to a depth of a few inches. Overwatering can be detrimental to the tree’s health and may lead to root rot.

Fertilizing

Crapemyrtle, once established, generally has low fertility requirements but can benefit from regular fertilization to promote lush growth and abundant blooming. Conducting a soil test is recommended to assess important soil parameters such as pH and nutrient levels, enabling precise fertilizer recommendations. Following a proper fertilization regimen optimizes plant growth while minimizing the risk of groundwater pollution through reduced runoff and leaching of excess nutrients. Based on the soil test results, it is advisable to incorporate lime, superphosphate, and other nutrients before planting to adjust pH and improve the soil’s nutritional balance. Crapemyrtle trees respond favorably to slightly acidic soil (pH 6.0-6.5) and general-purpose garden fertilizers can be used when needed or based on soil test. Alternatively, organic fertilizers like bone meal or rock phosphate can also be used to supplement nutrient needs.

Fertilizers are available in various forms, such as powder, granular, or liquid, and can be applied through different methods, such as broadcasting and placement of solid fertilizers, and fertigation using liquid fertilizers. Broadcasting involves the uniform distribution of fertilizers across the entire field either through basal application or top dressing. On the other hand, placement refers to the deliberate positioning of fertilizers at specific locations within the field. Broadcasting can be used prior to planting to adjust the overall nutrient balance of the soil, but it also promotes weed growth. Compared to broadcasting, placement is recommended for applying small amount of fertilizer, and it can be used to avoid weed pressure and lower nutrient runoff. For applying liquid (or soluble) fertilizers, fertigation is usually used, which the fertilizers are applied through irrigation water.

In the nursery production settings, an initial application of 50 lbs per acre nitrogen (N) to 6-to-8-inch soil can suffice the growing needs of woody plants such as crapemyrtle while minimizing nutrient runoff. In subsequent years, rather than broadcasting the fertilizer at the initial rate, the N fertilizer should be placed within the root zone as a side dress at the rate of 0.25 to 0.5 oz. N per plant (Smith, 2014). Alternatively, controlled-release fertilizer has also been developed for field application, allowing a single application to last the growing season.

During crapemyrtle container production, most growers in general incorporate controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs) in the substrate to provide necessary nutrients for plants to establish its root system and support new growth. Hence when transplanting a new crapemyrtle tree in the landscape, mixing fertilizers such as CRFs into the soil might not be necessary, or be handled as needed according to a soil test. In the landscape, crapemyrtles are generally very vigorous growing plants, but when growing in poor soil conditions might require occasional applications. For established crapemyrtle trees, fertilization might be performed as needed during the growing season, typically in spring to early summer when the tree is actively producing new growth. Fertilization in late summer should be avoided as it will interfere with the plants’ ability to harden off in the fall. Established crapemyrtle trees in landscape may not require fertilization if they are growing in nutrient-rich soil and receive regular rainfall, as they may be able to obtain the necessary nutrients naturally. Monitoring the tree’s growth and health can help determine if supplemental fertilization is necessary.

Propagation

Crapemyrtle can be propagated using various methods, including stem cuttings, root cuttings, or seeds. The most commonly used method is through semi-hardwood cuttings taken during late spring or early summer. In the southern US, the propagation rates of crapemyrtle through cuttings drop quickly by September. In northern states such as Michigan, the cutting propagation success starts dropping as early as July or August. Cuttings should measure three to six inches in length and have three to four nodes. It is advisable to remove the leaves from the lower half of the cutting, leaving a few leaves at the top. While crapemyrtle cuttings can root without hormones, rooting powder or solution can enhance rooting success and speed up the process. Once prepared, the cuttings should be inserted into a well-draining rooting medium and kept in a moist and shaded environment.

Root development usually occurs within three to six weeks while rooting success in cuttings varies across different times of the year. Cuttings taken during late spring to early summer typically exhibit rooting within three to five weeks, indicating this period as optimal for propagation efforts. Conversely, cuttings obtained in early spring show a notably lower rooting success rate. Additionally, cuttings derived from flowering plants or those taken in late summer are less likely to root effectively. Therefore, for optimal results in crapemyrtle cutting propagation, it is advisable to select cuttings during late spring to early summer.

Propagation by dormant cuttings has been used as a viable method in nursery production. Rooting success will be lower using this method, but it allows growers to continue production during slower seasons and increase production volume. 4-to-6-inch cuttings (approximately the diameter of a pencil) can be prepared and treated with a moderate IBA concentration before placing into a warm greenhouse with enough mist to prevent dehydration. The cuttings can be nicked or scarred on the basal end helps with IBA uptake and promoted callas growth.

For propagating crapemyrtle from seeds, collect mature seeds from fruit pods in the fall and sow them in a well-draining potting mix. Keep the soil consistently moist and warm, and seedlings should emerge within a few weeks. Whether using cuttings or seeds, it is crucial to maintain soil moisture and provide shade to prevent drying. Once the new plants have established roots, they can be transplanted to their permanent location in the landscape, preferably during dormant seasons such as winter (Wade and Williams-Woodward, 2009).

It is important to note that propagation practices can vary among different growers and nurseries. The decision on leaf removal during propagation often depends on balancing the need for photosynthesis and the need to reduce transpiration and conserve moisture. In the industry settings, the labor cost for certain propagation practices should also be taken into consideration. For example, Propagation by seed is never used for nursery production. Most commercial production is through asexual propagation. Seed propagation is useful in breeding programs to obtain new traits. Those seedlings of interest are asexually propagated. Commercial nurseries also seldom propagate crapemyrtles by root suckers.

Pruning

Crapemyrtle is known as a low-maintenance plant with little or no need for pruning when appropriate cultivar and correct placing were implemented. If necessary, pruning can be done for different purposes, such as promoting shape, thinning the tree, and maintaining size. While pruning is not essential for promoting flowering, it is known that proper pruning can lead to new vegetative growth that produce denser flower clusters (Gilman and Black, 2005) and higher number of flowers (Dihingia and Saud, 2016). For some cultivars, pruning to remove spent flower blossoms or the developing seed heads can stimulate new growth as well as more rounds of flower display (Gilman and Black, 2005; Wade and Williams-Woodward, 2009). However, over-pruning and incorrect pruning practices may damage the tree and produce undesirable plant architecture (Polomski and Shaughnessy, 2006).

Pruning is preferably done during the dormant season for crapemyrtle, typically in late winter or early spring, to avoid interfering with the blooming season. Since crapemyrtle produce flowers on new growth, pruning during the growing season can lead to loss of flower buds (Wade and Williams-Woodward, 2009). Pruning should be avoided in the fall, especially near the first frost, since it prevents plants going into full dormancy, leading to loss of cold hardiness of the crapemyrtle (Hayns et al., 1991).

Depending on the intended purpose, pruning can be done at early stages in the crapemyrtle’s development. For example, when pruning for tree form, the focus is on removing lower branches to create a clear trunk and a well-defined canopy. The main stem should be trained to grow straight and tall, while any lateral branches should be pruned back to encourage upward growth. The ideal tree form for crapemyrtle is a single-trunk or multi-stemmed tree with a rounded or vase-shaped canopy. Removing lower branches allows for better air circulation and reduces the risk of disease and insect infestations. It also helps to create a cleaner, more aesthetically pleasing look.

On the other hand, when pruning for a shrub form, the focus is on creating a full and bushy plant with multiple stems. This can be achieved by leaving the lower branches intact and pruning the upper branches to promote branching and fuller growth. The shrub form is also a suitable option for smaller cultivars or for those grown in containers. Regardless of the plant form (single-, multi-trunk, or shrub), it is helpful to periodically remove suckers as a part of maintenance for mature crapemyrtle in the landscape. Suckers are unwanted shoots that grow from the roots and base of the tree. Removing these suckers ensures that the crapemyrtle focuses its energy on growing upward instead of outward.

Dormant pruning of the plant to 3-4 inches above the soil has been shown to be effective in incorporating crapemyrtles into smaller garden landscapes, or to encourage flowering at a lower height. Such a method is particularly beneficial when the landscape design requires smaller flowering shrubs, ensuring that the crapemyrtles remain proportionate to the garden's scale. Dwarf and semi-dwarf varieties of crapemyrtle are especially responsive to this type of practice, producing lush, manageable growth suited to compact spaces.

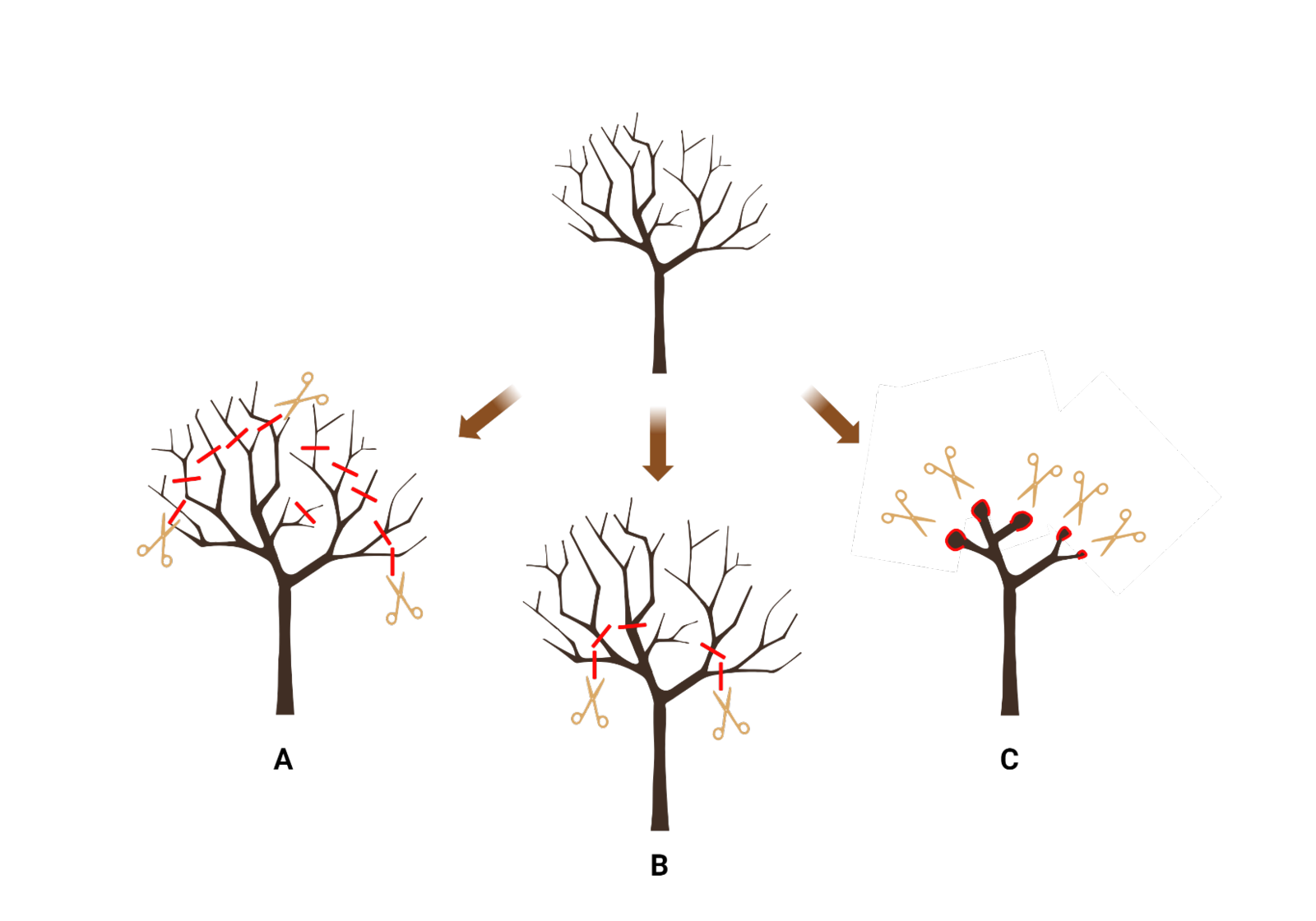

When it comes to maintaining crapemyrtle in the landscape, there are several pruning practices that were commonly used, including tipping, pollarding, and topping (Knox and Gilman, 2010). Tipping (also known as ‘tip pruning’, ‘rounding over’, or ‘pencil pruning’) is considered light pruning where only smaller-diameter branches on the outer edge of the canopy were removed (Figure 3). ‘Tipping’ practice can thin out the canopy by removing unwanted or dead branches with empty seed pods from the previous season while retaining the nature form of the crapemyrtle. However, tipping is very time consuming, thus it may be leading to the prevalence of more aggressive pruning practices such as pollarding and topping.

Pollarding and topping, on the other hand, are considered ‘hard pruning,’ where larger-diameter branches are removed. Pollarding is an annual pruning technique that involves making an initial cut on a multi-year-old branch. Subsequently, all sprouts that emerge each year are trimmed back to the original cutting area, creating a ‘pollard head.’ (Figure 3) Over time, the wound wood around the cut area swells, forming the pollard head storing significant energy for sprouting in the following season. Pollarding is typically done to confine plants to a specific size indefinitely, allowing crapemyrtle to regrow and maintain the same tree form each year.

Figure 3: Three different pruning methods for crapemyrtle include: (A) Tipping, where only smaller-diameter branches on the outer edge of the canopy are removed; (B) Topping, where large-diameter branches are cut; and (C) Pollarding, where crapemyrtles are trimmed back to the same cutting area each year, creating a bulbous growth referred to as a 'pollarding head.'

Similar to pollarding, topping (also known as heading, stubbing, rounding, or dehorning) removes large-diameter branches, but the cuts were not made to the original cutting area, thus no ‘pollard head’ is formed (Figure 3). The topping method results in the shortening of all branches, hence, can also be used to restrict the size of a crapemyrtle. Compared to other selective pruning methods, topping is the least time-consuming method, however, study has shown that topping creates unstable branching structure and decaying or dead branches in the canopy (Gilman and Knox, 2005).

It is generally advised to avoid over-pruning crapemyrtle, as it may be unnecessary and result in an unappealing appearance, particularly in winter and if the natural form of the tree is desired. The practice of ‘hard pruning’ such as topping can have negative effects on the health of the crapemyrtle, potentially leading to pest and disease issues (Appleton et al., 2009). While it is true that crapemyrtle flowers only on new growth each season, excessive pruning to remove empty seedheads from the previous season is unnecessary, as they will naturally drop when new growth emerges.

Container Production

Selecting Containers

Selecting the right container for crapemyrtle involves considering factors including the physical properties of the container (e.g., size, material, functionality, and drainage) as well as the planting time frame. Growing crapemyrtle in containers restricts and slows down their growth, which is desirable if a miniature-sized plant is desired due to limited space. Crapemyrtle can also be grown as a bonsai tree. However, it’s important to consider the mature plant size of the crapemyrtle, which varies greatly between different species or cultivars. Certain species of crapemyrtle, such as L. speciosa, are fast-growing plants that can reach up to 30 to 60 feet in height and approximately 30 to 40 feet in width (Gilman, Watson et al. 2019). Therefore, the container needs to provide ample room for the root system and accommodate the size and growth habit of the plant. An overgrown crapemyrtle in a container would easily topple over, especially when placed outdoors.

The effects of container size have a significant impact on the overall plant growth (NeSmith and Duval 1998). Moreover, the length of time the plant is likely to be spent in the container should be considered, as the transplanting timing affects greatly the vegetative growth on the finished plant (Knight, Eakes et al. 1993). In general, plants grown in larger containers have greater plant leaf area, and shoot and root biomass (Cantliffe 1993). Therefore, when the goal is to encourage growth, it is necessary to transplant crapemyrtles into larger containers once the plants reach their maximum growth potential in the original container. To transplant small plants or liners (containers < 8 inches in diameter) into larger containers, it is recommended to choose containers that are 1 to 2 inches wider than the current root ball. For transferring larger plants (containers > 10 inches in diameter), choosing 2-inches to 3-inches wider than the plant’s root ball is ideal (Moore and Bradley 2018).

Most crapemyrtle sold by the nursery are planted in plastic containers. Plastic containers are lightweight, durable, and easy to handle, making them a practical choice for long-term use. Retail garden centers generally offer a variety of container sizes including trade #1 (2.5L), 2 gallon (g), 3g, 5g, 7g, 10g, and 15g, ranging from 15.24 to 44.45 cm (6–17.5 in) in diameter, allowing flexibility in choosing the appropriate container for different stages of plant growth. According to a recent survey, the three most popular sizes for crapemyrtles are 15 g, 30 g, and 45 g (Marwah, Zhang et al. 2021). For nurseries, the largest volume of units of crapemyrtles sold are 2 and 3g. While 1-gallon size provides the lowest price point, consumers are looking for a balance between cost-effectiveness and plant size during their purchase.

Plastic containers also retain moisture better than clay pots, which can be advantageous in hot and dry climates (Moore and Bradley 2018). There are also plastic air-pruned containers that promote a more fibrous root system, which greatly affects a plant’s health and future establishments (Cooley 2013). Additionally, cupric hydroxide-treated (product trade name: SpinOut™) containers were found to be effective in controlling root circling and deflection when growing crapemyrtle, with no observed negative symptoms (Beeson Jr and Newton 1992).

While rarely used in commercial production settings, there are other container types utilizing different materials such as clay, wood, and fabric, available for consumers. Clay and wood containers provide better breathability for the roots as they allow air exchange through the container walls, preventing root suffocation and promoting overall plant health. They also have an aesthetic appeal that enhances the visual appeal of the landscape. However, clay pots are heavier and more prone to breakage compared to other materials. On the other hand, wood containers, such as cedar or redwood, provide natural durability (up to ten years) and add a rustic look to the landscape (Moore and Bradley 2018).

Fabric containers, known as grow-bags, are lightweight, portable (foldable), and offer excellent drainage. Fabric container is a hybrid form of production system between field and container production, as the container can be used above ground (similar to other types of container), or buried under soil, leaving only the top inch of the fabric exposed above ground (Gilman, Knox et al. 1994). Grow-bag confines plant root within its porous fabric barrier, leading to the effects of root pruning and root branching. However, a study compared Natchez crapemyrtle transplanted from field and grow-bag and found mostly equivalent plant performance in these two productions (Tilt, Gilliam et al. 1992). Nevertheless, fabric containers offer several potential benefits over traditional field production. They enable plants to retain a greater portion of their roots during transplanting, which reduces stress on the plant. Furthermore, fabric containers simplify the logistics of nursery operations, including the shipping of bags to the nursery. They also contribute to a reduction in the shipping weight of the finished plants, making the transportation process more efficient.

The decision to utilize alternative production systems, such as grow-bags, may depend on the field soil conditions, which determine the ease of traditional field harvesting. Regardless of the material, it is crucial to ensure that containers have sufficient drainage or can be modified to allow excess water to escape. Adequate drainage prevents waterlogging, which can lead to root rot and other plant health issues.

Substrates

The media used to grow container plants is generally referred to as ‘substrate’, ‘potting mix’, and ‘growing media’, and they do not usually contain field soil. Field soils are generally too heavy and do not have enough pore space and drainage when placed inside container, thus unfit for container plant production. For cultivating container-grown crapemyrtle, proper substrate preparation includes the considerations of the substrate’s physical properties [e.g, total porosity, container capacity (i.e., water holding capacity), and air-filled porosity] and chemical properties (e.g., pH, electrical conductivity, and nutrient levels).

The substrate composition should have the ability to retain moisture while promoting proper drainage to prevent waterlogged conditions and provide adequate aeration for the roots. A typical substrate mixture for container-grown crapemyrtle includes a combination of organic and inorganic components such as peat moss or coconut coir for moisture retention, perlite or vermiculite for improved aeration, and pine bark or composted pine fines for structure and nutrient availability.

For outdoor container nurseries where large amounts of substrates are required, the input cost and availability of raw materials are also important factors to be considered. The most common substrate adopted by the U.S. nurseries include a mixture of pine bark, sphagnum peat moss, and sand, at varying ratio. Aged pine park (particle size ranging from 0.5 to 16 mm, with up to 30% under 0.5 mm) is generally preferred compared to fresh pine bark due to the enhanced water holding capacity (Bilderback 2017). In general, growers use a recipe of 80% to 100% aged pine bark, with addition of sand or peat moss to make up the rest (Braman, Chappell et al. 2015, Bilderback 2017). Sometimes sand and soil are added to increase the weight, which reduces container tip-over, but can also introduce pathogens. However, pine bark, especially when aged, is limited and time-consuming to acquire. Therefore, alternative materials to pine bark have been increasingly studied and used to lower the production cost.

Most alternative substrates are organic wastes such as shredded coconut husks (coir), rice hulls, peanut hulls, pecan shells, and other composted wastes (e.g., yard wastes, animal wastes, and hardwood bark). These organic matters need to be fully composted before using since unstable organic material tend to decompose and losing volume rapidly.

High wood-fiber content substrates such as clean chip residual (CCR), ground pine chips (PC), and WholeTree (WT) has been evaluated for their potential replacement for pine bark (PB) in crapemyrtle container production. Boyer, Gilliam et al. (2009) used CCR at varying sizes [screening size up to 3.18 cm (1.25 inch)] to grow ‘Hopi’ and ‘Natchez’ crapemyrtles in #1 container and found no difference in performance between the plants grown in CCR and PB. Marble, Fain et al. (2012) also demonstrated that both CCR and WT could be used to produce equivalent marketable crapemyrtle compared to PB. On the other hand, Wright, Browder et al. (2006) showed that crapemyrtle were larger when grown in PB compared to PC, which is attributed by the lower nutrient availability in PC. These studies suggest that alternative wood-based substrates could potentially replace the declining supply of PB, but testing should be done prior to the implementation of these materials to determine proper fertility adjustment needed.

In recent years, substrate stratification, a practice of creating ‘layered’ substrates inside containers, has been described as a potential solution for improving resource management in container crop production. Fields, Criscione et al. (2022) found that ‘Natchez’ crapemyrtle had greater root dry weight when grown in stratified substates where finer substate was placed atop of the coarser particles, compared to the unstratified controls. The placement of coarse particles at the bottom half of the container was shown to improve drainage and uniformity of water retention throughout the container profile. Similarly, adding drainage material like gravel or perlite to the bottom of the container promotes proper drainage in the containers.

Maintaining the appropriate pH and electrical conductivity (EC) levels in the substrate is crucial for optimal plant growth in containers. While the natural or properly aged pine bark is generally suitable for crapemyrtle growth (pH range 5.0 - 6.5), testing should be done to determine the pH and EC prior to the mass utilization of the substrate. The reading of pH and EC of the substrate can be obtained by testing 1 cup (236.6 mL) of the substrate mixed with distilled water, using a pH and conductivity testing pen or meter. Ideal pine bark are expected to have a low pH between 3.9 to 6.0 and conductivity range between 0.2 to 0.5 dS/m (mmhos/cm) (Bilderback 2000, Braman, Chappell et al. 2015). The pine bark should not be used if low pH (e.g, pH < 3.8) or high conductivity reading (e.g, 1.5 - 2.5 dS/m) are found as they are potential indicative of unfinished decomposing process and active anaerobic respiration inside the substrate pile. Once plants have established roots in the substrate, monitoring practices such as pour-through technique can be used to maintain optimal plant health and growth. The pour-through technique involves watering the plants sufficiently so that the excess water, or leachate, drains out and can be collected for analysis. By examining the leachate, growers can evaluate the nutrient content and salt accumulation within the container media, and adjust the fertilization as needed to correct any deficiencies or imbalances.

Good sanitation practices in storing and handling substrate are important to eliminate weed seeds, pests, and pathogens that could hinder plant growth. This can be achieved by using commercially available sterilized substrates and proper sterilization of production surface. 10% sodium hypochlorite solution or other commercially available disinfectant can be used to clean recycled containers.

For container nursery production, implementing proper sanitation practices helps minimize the risk of soil-borne diseases, ensuring the health of container-grown crapemyrtle. Bulk substrate inventories should be stored on a concrete slab at the highest elevation in the nursery to avoid contamination from the runoff from the growing areas. The potting bark inventory piles should be kept moisten, under 10 feet, and turned periodically (at least every 3 to 4 weeks), to prevent fire hazards. Frequent turning and mixing of the moisten bark also help prevent fungal colonization of the medium (Braman, Chappell et al. 2015).

Irrigation

Proper irrigation is crucial for the successful container production of crapemyrtle. The frequency and amount of watering depend on various factors such as container size, weather conditions, and plant growth stage. Generally, crapemyrtle planted in containers require more frequent watering than those in the ground. Containers tend to dry out more quickly than the ground, so daily watering may be necessary during hot and dry periods. It is important to monitor the moisture level of the substrate and water the plant when the top inch of substrate feels dry. When growing media containing peat moss or pine bark is used, it is important to avoid the media to dry out. Pine bark-based substrate can tolerate a certain degree of overwatering to suffice the irrigation needs, however, frequent over watering leads to the concern of nutrient leaching from the container (Braman, Chappell et al. 2015).

Irrigation types include overhead irrigation for smaller plants (e.g., in #1, #3, and #5 containers) or liners, while spray stakes or drip irrigation are primarily utilized for larger plants (e.g., in #7, #15, and #25). Best management practices commonly adopted by growers include cyclic irrigation, collection of runoff water, watering in the morning, and implementation of grass strips between production and drainage areas (Garber, Ruter et al. 2002).

Cyclic irrigation or cyclic microirrigation are irrigation practices to apply multiple rounds of subvolume of water instead of applying the total volume at a single time. Cyclic irrigation has several advantages in terms of resource allocation, including reduction of irrigation water input, minimizing water runoff, and reduction of nutrient leaching, compared to continuous irrigation (Fare, Gilliam et al. 1994). For crapemyrtle, research showed that cyclic irrigation using the same volume of water has led to increased plant height, trunk diameter, and shoot dry weight, compared to the controls where irrigation volumes were provided at once (Beeson Jr and Haydu 1995).

Irrigation should aim to provide deep and thorough watering to encourage deep root growth. This helps the plants become more resilient to drought conditions. Water should penetrate the entire root ball and reach the bottom of the container. Avoid shallow and frequent watering, as it can lead to shallow root development and increase the risk of water stress. The leaching fraction from containers (irrigation drainage/total volume applied) and irrigation uniformity should be monitored to evaluate the efficiency of the irrigation system. Ideal leaching fractions for container crapemyrtle production should be between 0.15 and 0.25, but the value might be subjected to large fluctuation due to multiple factors including seasonal changes and pruning practices needed for crapemyrtle (Million and Yeager 2019, Million and Yeager 2021). Automated irrigation systems have been evaluated in recent years and may be implemented by nurseries to effectively lower the water input and maximize plant productivity.

Irrigation regimes may be adjusted according to the specific needs of the crapemyrtle variety and close monitoring. While current research that compares drought resistance levels for other crapemyrtle species and cultivars is limited, crapemyrtles are generally considered to be drought tolerant with little variation in different cultivars. Harp, Chretien et al. (2021) evaluated five ‘Ebony’ series crapemyrtle and ‘Centennial Spirit’ for their performance under low input landscape and reported no drought stress among all tested cultivars. On the other hand, (Cabrera 2009) reported the different salinity tolerance levels between ‘Pink Lace’, ‘Natchez’, and ‘Basham’s Party Pink’, and ‘Basham’s Party Pink’ was rated as having the most salt tolerance among the three cultivars. Therefore, monitoring the plants’ response to irrigation and adjusting watering practices accordingly is crucial to maintain optimal plant health.

Mulching the surface of the container can also help conserve moisture and reduce evaporation. Applying a layer of organic mulch, such as bark chips or straw, around the base of the plant helps to retain soil moisture, regulate soil temperature, and suppress weed growth. There is also an increasing number of growers adopting rice hulls as the mulching material. Studies showed that applying mulch on growing media allows for lowering irrigation volumes and can lead to increased gas exchange and overall plant growth of containerized crapemyrtle (Montague, McKenney et al. 2007).

Fertilization

Fertilization provides the necessary nutrients for healthy growth and abundant flowering of crapemyrtle grown in the container. Under-fertilization results in nutrient deficiencies and stunted growth. On the other hand, over-fertilization can lead to excessive vegetative growth at the expense of flowering and may even cause nutrient imbalances or burn the roots. Here are some key considerations for fertilizing crapemyrtle in container production.

Incorporating controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs) into substrates is a standard practice for fertilizing container plants over an extended period, providing consistent nutrient support to the plants. For general consumers looking to fertilize container-grown crapemyrtle, applying an all-purpose fertilizer with a balanced ratio of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) is a good starting point. Fertilizer formulations such as 10-10-10 NPK with micronutrients (e.g., boron, iron, manganese, zinc, sulfur, magnesium, etc.) provide a well-rounded nutrient supply to support overall plant growth and flower production. For growers producing crapemyrtle at large scale, however, both the substrate and irrigation water should be tested to determine a fertilization regime. Substrates, substrate leachate (~ 50 mL) or plant tissue samples can be submitted to a commercial or university laboratory for a complete analysis of the nutrient levels to obtain specific guidance on fertilization needs (UMass 2023).

For growers, bark substrates in container production must have a complete package of micronutrients, and topdressing new crops of container production with CRFs is common. It is generally recommended to utilize CRFs with a fertilizer nutrient ration of approximately 3:1:2 (N:P:K) for container grown plants (Yeager, Gilliam et al. 1997). Best management practices recommended to supplement substrate with nitrogen at a rate of 3 grams per 1 gallon container (Bilderback 2017). For example, if a fertilizer containing 18(%) N is used, a total of 16.7 g of such fertilizer should be added to a 1-gallon container. Furthermore, studies have shown that fertilizer grades with lower amount of P and K, such as 18-1.7-6.6 and 19-2.6-10.8, are suitable for production of crapemyrtle in container (Shreckhise, Owen et al. 2020, Shreckhise, Owen et al. 2022). However, further lowering the P level in the fertilizer (using a 18.4-1.4-10.2 formulation) was found to negatively affect the shoot dry weight and overall plant quality (Shreckhise, Owen et al. 2022). Pine bark-based substrates were known to be prone to P leaching from containers during irrigation. Therefore, as suggested by Shreckhise, Owen et al. (2020), amending substrate with dolomite and a sulfate-based micronutrient fertilizer is considered a best management practice for crapemyrtle container production.

The placement of CRFs inside the container was found to influence the crapemyrtle growth. (Martin and Ruter 1996) has demonstrated that placing CRF at the north exposure of container has led to the increased plant size of crapemyrtle grown under outdoor nursery conditions. This phenomenon was attributed to the root growth pattern and the root zone temperature inside a sun-exposed container, and thus this practice could be most beneficial for crapemyrtle production in a hot and arid climate area.

When soluble fertilizer is incorporate in the irrigation water, it is important to consider not to utilize high concentration especially when constant feed fertigation is implemented. Cabrera and Devereaux (1999) has reported that 60 ppm N application was optimal in promoting the growth of ‘Tonto’ crapemyrtle, while higher concentration was shown to cause growth depression. Another study conducted by (Schluckebier and Martin 1997) showed that ‘Muskogee’ crapemyrtle had the best growth response to the fertigation with 50 microliter/Liter humic acid extract, but the higher concentrations (150 or 300 microliter/Liter) caused growth inhibition. Fertilization at a higher rate was also known to cause reduced flowering in crapemyrtles (Harrison 2006, Buxton 2017).

In addition to regular fertilization, it’s beneficial to supplement with micronutrients as needed. Micronutrients, such as iron, manganese, and zinc, are essential for proper plant growth and development. These can be provided through foliar sprays or incorporated into the potting mix, depending on the specific needs of the plants. For example, the foliar application of Moringa leaf extract was shown to promote growth and protect crapemyrtle plants against salt stress (Soliman and Shanan 2017).

Timing is important when fertilizing crapemyrtle in containers. Begin fertilization in early spring, once the plants have started to actively grow. Continue fertilizing throughout the growing season, typically until early summer. Avoid fertilizing during winter or periods of dormancy, as excessive vegetative growth prior to dormancy causes winter damage.

Regularly monitor the plants’ response to fertilization and adjust the fertilizer application as needed. Assess the overall growth, foliage color, and flower production. If the plants show signs of nutrient deficiencies or excessive growth, consider adjusting the fertilization regimen accordingly.

Pruning

Pruning practice for containerized crapemyrtle promotes plant uniformity, which is beneficial for nursery production (Zajicek, Steinberg et al. 1991).

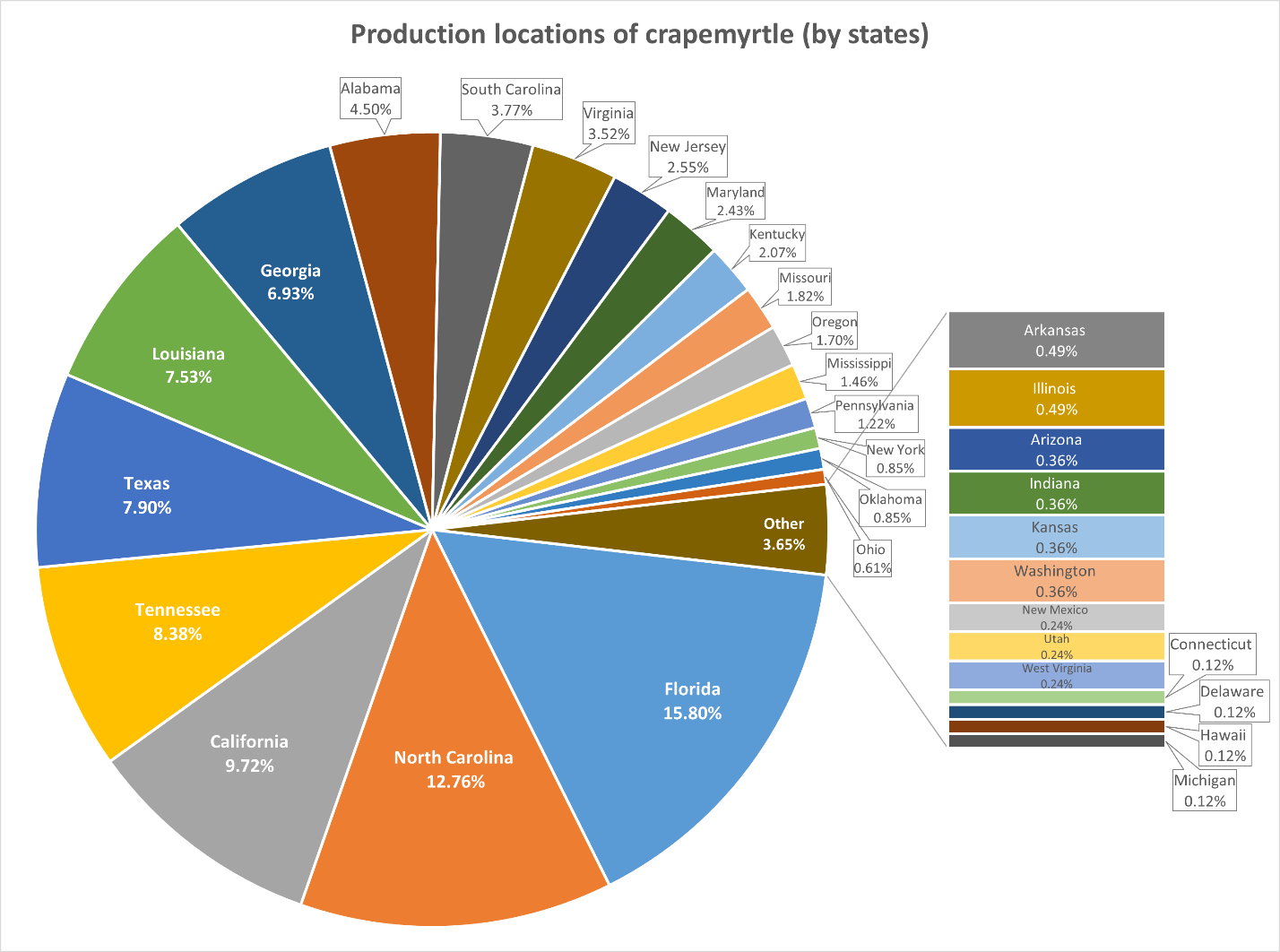

Production Counties

The USDA NASS has documented businesses that grew and sold $10,000 or more of crapemyrtle during each census year since 1997. The number of operations producing crapemyrtle has fluctuated between 800 and 1100 across the United States over the last two decades. As of 2019, there were a total of 823 operations generating crapemyrtle sales in the United States, with 650 involved in wholesale and 269 in retail sales. Crapemyrtle production is conducted in 29 states in 1998 and increased to 33 states in 2019, with most states located in the southeastern part of the continental United States. Florida has the greatest number of operations involved in the production or selling of crapemyrtle, followed by North Carolina, California, Tennessee, Texas, Louisiana, Georgia, and Alabama, which together account for approximately 75% of all producers in the United States (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The percentage of crapemyrtle producers in different U.S. states in 2019.

Counties:

Counties:

Counties:

Counties:

Counties:

Counties:

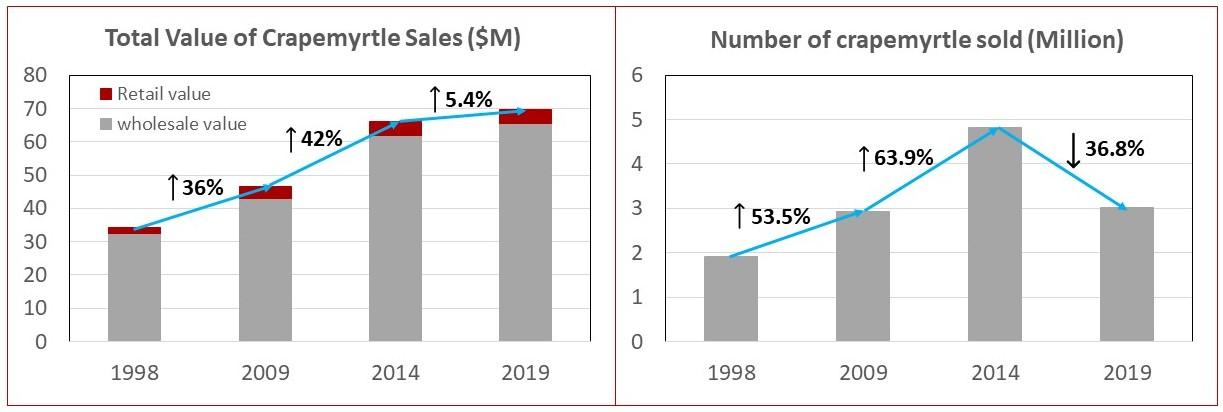

Production Facts

In terms of economic value, crapemyrtle production has an irreplaceable role to play in the green industry. According to the latest USDA report, crapemyrtle generates an increasing market value (annual wholesale values and retail value) of up to $70 million per year, which almost doubled the number since 1988 (USDA, 2001, 2009, 2014, 2019). In 2019, 3.03 million plants with a combined value of $69.57 million were sold (figure 5).

Figure 5: Total sales of crapemyrtles in 1998, 2009, 2014, and 2019.

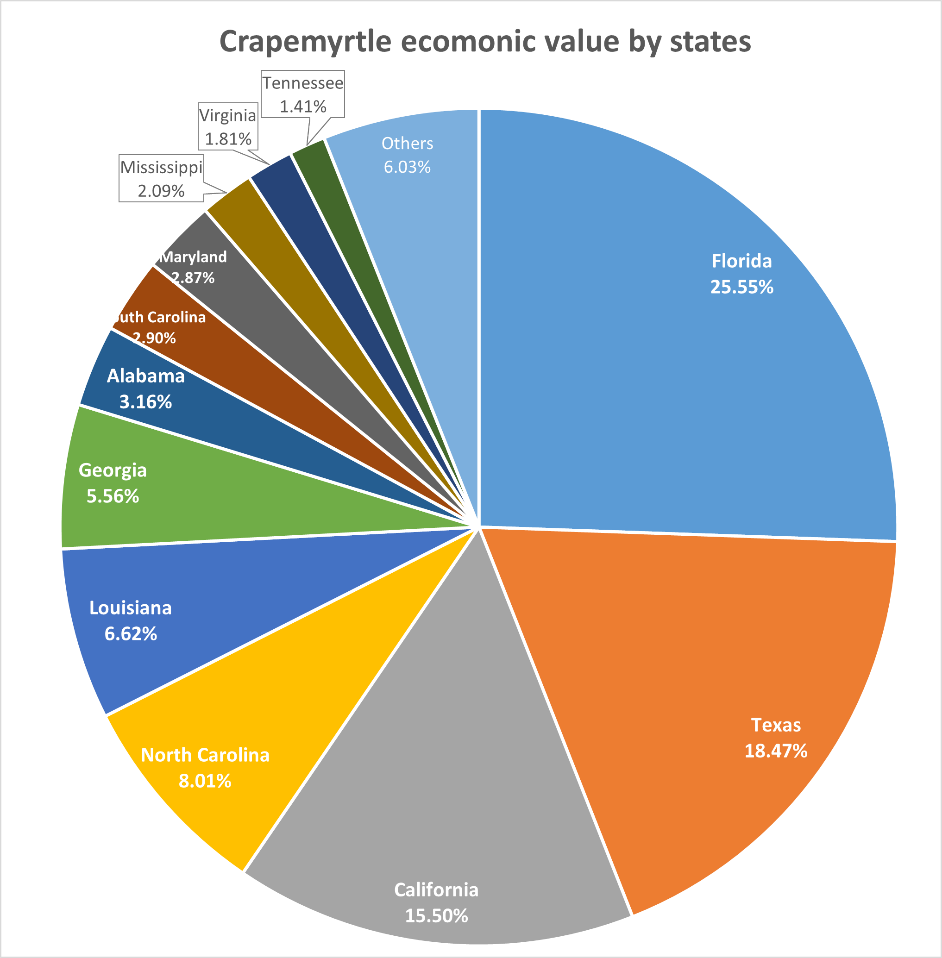

Figure 6: Crapemyrtle ecomonic values in different U.S. states.

IPM Practices

Crapemyrtle Bark Scale (Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae)

Introduction of crapemyrtle bark scale

Crapemyrtle bark scale (CMBS; Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae), an invasive polyphagous sap feeder in the United States, has spread across 17 U.S. states in less than two decades, posing potential risks to the Green Industry.

Crapemyrtle bark scale is a hemipterous insect under the superfamily of Coccoidea (scale insects), which is closely related to other piercing-sucking insects such as mealybugs (Pseudococcidae), aphids (Aphididae), whiteflies (Aleyrodidae), and psyllids (Psyllidae). According to previous studies and observations, the number of CMBS generations within one-year ranges from two to four depending on the climate zones. In the Southeastern United States, CMBS-infested plants can be found in the field year-round, with up to four generations of CMBS being observed in Dallas, TX in 1 year. However, the lack of in-depth characterization of CMBS biological parameters, such as developmental stages, reproductive behavior, and fecundity, limits the research capacity to investigate controlling strategies based on insect biology and physiology.

Life cycle

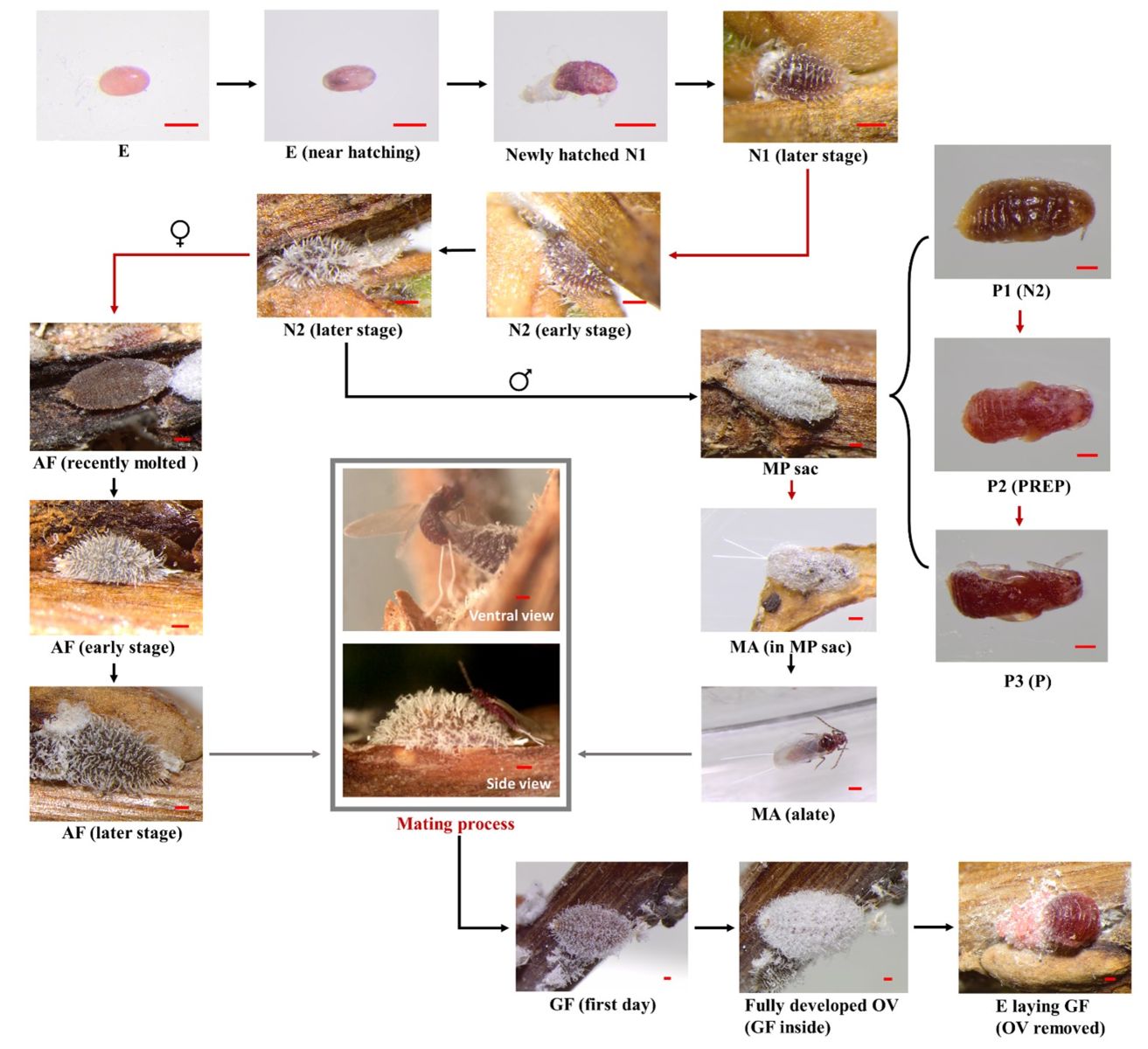

The life cycle duration of CMBS varies according to different factors, such as temperature and host plant genetics. The average duration of one generation was estimated to be between 79 to 147 days under lab conditions (Xie et al., 2023). Under field and favorable environments, the mean generation time might be shorten, and it was observed that two to four generations of CMBS can occur in one year depending on the geological locations (Gu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). The life cycle of CMBS males started from egg, which takes around 11 days to hatch when incubated under lab conditions at 25 °C. The developmental stages for individual insects, such as the 1st and 2nd instars, can be determined by monitoring molting events or by keeping track of the insect exuviae. The duration of 1st and 2nd instar stages are about 14 to 17 days and 29 to 68 days, respectively, depending on the different crapemyrtle used as host. The development of the male pupa was characterized as a three-step process (P1, P2, and P3 stages). Firstly, a P1 stage has been identified, as a 2nd instar forms the elongated ‘cocoon’ structure typically identified as a male sac in the field (Figure 7). Before P1, 2nd instar nymphs typically retract and detach their stylets from the plant and become mobile. Within a short period (24h), the male 2nd instar will relocate until finally settle down at a location, then start excreting wax to form the white male sac. After P1, the 2nd instar will pupate and push out the exuviates through the rear opening of the male sac. The duration of P1, P2, and P3 is around 4-8, 3-5, and 5-7 days, respectively. Hence, a total of three exuviates will be pushed out from the male sac before adult male emergence. After the molting of the pupa, the adult male usually stays in the pupa sac for several days before emergence. Once exiting the pupa sac, the adult male immediately roams the surrounding environment, presumably searching for the adult female’s presence. The development of CMBS males is complete metamorphosis, as pupa and adult male stages can be identified (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Detailed life history of crapemyrtle bark scale, Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae. E: Egg, N1: first-instar nymph, N2: second-instar nymph (N1 and N2 are indistinguishable in male and female), AF: adult female (or female third-instar nymph), MP sac: male pupa sac (consist of three stages: P1, P2, and P3), PREP: prepupa, P: pupa, GF: gravid female, OV: ovisac. Scale bars: 200 μm. Arrows represent chronological progression. Red arrows: molting events. Gray arrows and outline: adult males emerge and locate sessile adult females to perform the mating process (Xie et al., 2022).

Population dynamics

From 2015 to 2017, a monitoring program was implemented across Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas to track the seasonal population trends of CMBS. This program utilized double-sided tape wrapped around selected branches on a weekly basis. This method proved effective for capturing newly hatched crawlers, thereby revealing patterns of crawler activity throughout the year. The initial surge in crawler activity consistently occurred between March 26th and May 22nd in all studied locations and years, followed by several additional peaks, suggesting the presence of multiple generations of CMBS within a single year. The monitoring program also showed no significant difference in crawler activity levels between the upper and lower branches of crapemyrtle trees throughout the season (Vafaie et al., 2020).

Mating behavior

Mating behavior was observed between adult males and adult females, which is an essential process required for reproduction. Newly emerged adult females typically remain mobile for a short period before settling down at a suitable location to feed on the plants. Thus, most adult females become sessile for the rest of the life cycle, while the alate adult male (once located the female) would initiate the mating process by taping the dorsal side of the female. Upon stimulation, the female reacts by lifting and retracting the rear end of her abdomen to accept copulation. The male then proceeds to curve its abdomen down and direct its genitalia to contact the ventral side of the female abdomen, where sperm transfer could be occurring (Figure7). After the mating process is completed, a reproductive female can be confirmed as the female develops its typical white ovisac structure (Figure 7). As a newly emerged adult female gaining its size, it might be undergoing development for sexual maturity as various adult preproduction periods were recorded. Therefore, depending on the female ages, it would take from 2 to 11 days before the development of ovisac could be observed. Shortly after the ovisac is developed (2-3 days), a female would start laying eggs, and the reproduction period can last up to 10 days.

Feeding behavior

As a sap-sucking insect, the feeding behavior of CMBS involves penetration of the plant epidermis and cortex tissues (using their mouthparts/stylets) to access the nutrient and water content in plant phloem and xylem. The Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) technique enables the real-time monitoring of the insect's probing activities in plant tissues by analyzing the generated EPG waveforms. Five distinct EPG waveforms—C, potential drop, E1, E2, and G—have been identified for CMBS on the validated host plant, L. limii (Wu et al., 2022). Waveform C indicates the stylet pathway phase, during which the insect begins probing and carrying out extracellular stylet pathway activities. At this stage, sudden changes in voltages (potential drops) were observed, suggesting insects are actively puncturing living plant cells using stylets. Following the stylet pathway phase, the E and G waveforms signify successful access to the phloem and xylem, respectively, indicative of successful feeding activity. Consequently, the insect's difficulty or ease in accessing the phloem and xylem is correlated with the plant's resistance level to CMBS. This resistance level can be effectively assessed using the EPG technique, providing a valuable tool for evaluating a plant's susceptibility to CMBS infestation.

CMBS alternative hosts and feeding preference

Crapemyrtle bark scale has long been reported with a fairly wide host range. Online insect databases such as Scalenet has accumulated a good amount of host information for CMBS. However, recently, as the distribution of CMBS continues to expand beyond its native regions, more specifically in the United States, concerns have been raised regarding the expanded host range for CMBS beyond Lagerstroemia, and the potential threats that CMBS poses to the native and economic important plants in the United States.

To address these issues, several studies has been conducted on the feeding preference and host range of CMBS. Greenhouse trials confirmed quite a few species as CMBS hosts, which provided different/additional findings to the previous knowledge regarding CMBS hosts. Here is a summarization of the current knowledge on CMBS hosts.

Greenhouse trials

Multiple greenhouse trials were conducted between 2016 and 2020. All tested plants species were inoculated with CMBS-infested crapemyrtle twigs. CMBS infestation was identified as the presence of both male pupae and gravid female ovisacs during our experimental period, indicating the ability of CMBS to complete life cycle and reproduction on test plants.

For the economic plants in the United States, the infestations of CMBS were confirmed on apple (Malus domestica), Chaenomeles speciosa, Disopyros rhombifolia, Heimia salicifolia, Lagerstroemia ‘Spiced Plum’, M. angustifolia, and twelve out of thirty-five pomegranate cultivars. However, the levels of CMBS infestation on these test plant hosts in this study are very low compared to Lagerstroemia and may not cause significant damage. No sign of CMBS infestation was observed on Rubus ‘Arapaho’, R. ‘Navaho’, R. idaeus ‘Dorman Red’, R. fruticosus, Buxus microphylla var. koreana × B. sempervirens, B. harlandii, or D. virginiana in 2019. Although in a follow-up study with increased CMBS inoculation, one gravid female ovisac was observed on D. virginiana in 2020.

In this study, compared to crapemyrtle, all other species had very LOW number of scales, if any. For example, at its peak L. ‘Spiced Plum’ had 600 male pupae, Heimia had about 25 and all others had less than 10 (or even 5). Manuscript on this study ‘Feeding Preference of Crapemyrtle Bark Scale (Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae) on Different Species’ was published in June 2020 (https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/11/7/399).

Table 1 below summarized all our tested plants in four categories: Severe, Moderate, Minor, and None depending on the level of infestation recorded during our CMBS feeding experiments.

Table 1 Summarization of the crapemyrtle bark scale hosts with different levels of infestation.

|

|

Level of infestationX |

|||

|

|

Severe |

Moderate |

Minor |

None |

|

Plant species |

Callicarpa americana ‘Bok Tower’ |

Callicarpa acuminata |

Callicarpa bodinieri ‘Profusion’ |

Buxus harlandii |

|

Callicarpa dichotoma ‘Issai’ |

Callicarpa japonica var. luxurians |

Chaenomeles speciosa |

Buxus microphylla var. koreana × Buxus sempervirens |

|

|

Callicarpa longissima ‘Alba’ |

Callicarpa pilosissima |

Disopyros rhombifolia |

Ficus pumila |

|

|

Lagerstroemia ‘Spiced Plum’ |

Callicarpa randaiensis |

Disopyros virginiana |

Ficus roxburghii |

|

|

Lagerstroemia caudata |

Callicarpa salicifolia |

Ficus tikoua |

Rubus ‘Arapaho’ |

|

|

Lagerstroemia fauriei ‘Kiowa’ |

Heimia salicifolia |

Glycine max |

Rubus ‘Navaho’ |

|

|

Lagerstroemia limii |

Hypericum kalmianum |

Malus angustifolia |

Rubus fruticosus |

|

|

Lagerstroemia subcostata |

Lagerstroemia speciosa |

Punica granatumY |

Rubus idaeus ‘Dorman Red’ |

|

|

|

Lythrum californicum |

|

|

|

|

|

Malus domestica |

|

|

|

|

|

Spiraea japonicaZ |

|

|

|

X Levels of CMBS infestation were defined as: Severe (>100 female ovisacs per plant), Moderate (10-100 female ovisacs per plant), Minor (<10 female ovisacs per plant), and None (no CMBS pupae or ovisacs).

Y twelve out of thirty-five pomegranate cultivars were confirmed with minor CMBS infestation

Z need to be confirmed through DNA identification.

Host suitability among Lagerstroemia

The primary hosts of CMBS, as where CMBS got the common name from, are considered to be crapemyrtle or Lagerstroemia. However, other than the previously reported L. indica and L. fauriei, which are the most popular parentage of commercially available Lagerstroemia cultivars, the host suitability for CMBS among many other species in this genus remained unknown.